Posts Tagged ‘Welfare State’

Universal Credit “Has not Worked” – Labour.

While we are waiting for the Budget this week…

No clear answer yet:

Shadow Chancellor Anneliese Dodds says Universal Credit system needs radical reform but for now the £20 uplift must be retained during the pandemic

Shadow Chancellor Anneliese Dodds has declared that Universal Credit “simply has not worked” and should be scrapped.

The call from Labour’s finance chief comes as claimants wait to hear if a coronavirus top-up on the benefit – £1,040 a year, equivalent to £80 a month or £20 a week – will be extended into the next financial year

Ms Dodds said the temporary rise for six million Brits must be “maintained during the pandemic” but in the long term, the welfare scheme must be replaced.

She spoke about Universal Credit on the BBC’s Andrew Marr Show, where she said: “In the near term what we’ve got to do is be clear to families that in the middle of a pandemic, they should not be seeing £20 less a week coming in when they’re struggling.

“In the longer term, what we really need to see is radical reform, scrapping that Universal Credit system because it simply has not worked for families.”

Today:

h

Calls for new Beveridge Report: building a decent welfare system

This was on Channel Four last night:

These serious calls have been made in the last few days.

What British politicians won’t admit – we need to transform the welfare state

A conversation about a fundamentally different welfare state ought to fall two ways: between immediate answers to the cruelties of our current systems, and longer-term ideas about how to completely reinvent it. The former might include an end to universal credit’s built-in five-week wait, the abolition of the cruel and arbitrary benefit cap, and no more sanctioning. It should extend to a recalibration of housing benefit so that people – including key workers – can afford to live in even high-cost areas, a watershed rise in our miserable rates of statutory sick pay, and the upgrading of the minimum wage and national living wage to the so-called real living wage (£9.50 across the UK and £10.85 in London), with an ongoing link to inflation.

Louise Casey: ‘Are we ever going to create a Britain for everyone?’

The former homelessness tsar thinks we need big, radical reform to tackle hunger, rough sleeping and poverty. And she has a plan

by Rachel Cooke“We need to move into Royal Commission territory,” she says. “A new Beveridge Report [drafted by the economist William Beveridge in 1942, this was the document that led to the founding of the welfare state]. That’s the kind of thing I’m talking about.” Crikey. Is this a job she would like to take on herself? I look at her steadily, wondering if she’s going to indulge in a bout of it’s-not-for-me-to-say. But, no. She doesn’t much go in for let’s pretend. “Yes, I’d love to be part of that,” she says. “Government can, if it wants to, do something on a different scale now. The nation has been torn apart, and there’s no point being defensive about that. We’ve got to gift each other some proper space to think. We’ve got to work out how not to leave the badly wounded behind.”

….

We can get there quite quickly,” she says. “By March, there will be 6 million people on universal credit [in October, there were 5.7m]. Almost 4 million people are furloughed, and those still working are on less income [in a survey by the Resolution Foundation, 26% of adults reported suppressed wages during the first lockdown]. Unemployment has doubled [it stood at 1.72 million in November 2020], and will keep rising. Two million people are still on legacy benefits – which means they didn’t get the £20 uplift that came with universal credit. Then you add in the 5 million people who are in debt [42% of adults report using at least one form of borrowing to cover everyday living costs].

….

Pre-pandemic, there were 280,000 homeless in England and Wales. Earlier this month, the government announced that the ban on bailiff-enforced evictions, which protects private renters, would be extended to the end of March. But it will end eventually. “At which point, family homelessness will rise,” says Casey. “If 25% of your population is affected, then you can’t just tweak old policies, working out the least expensive, least challenging thing that can be done. You need big new policies.”

Most of us will have views on this!

Warning about the impact of cuts to Universal Credit.

The National Government of 1931 cut benefits of insured workers by ten per cent.

I mention this because it was something that people, including my Glaswegian father, remembered for years afterwards, Glasgow was of course on the places heavily affected by mass unemployment during the depression.

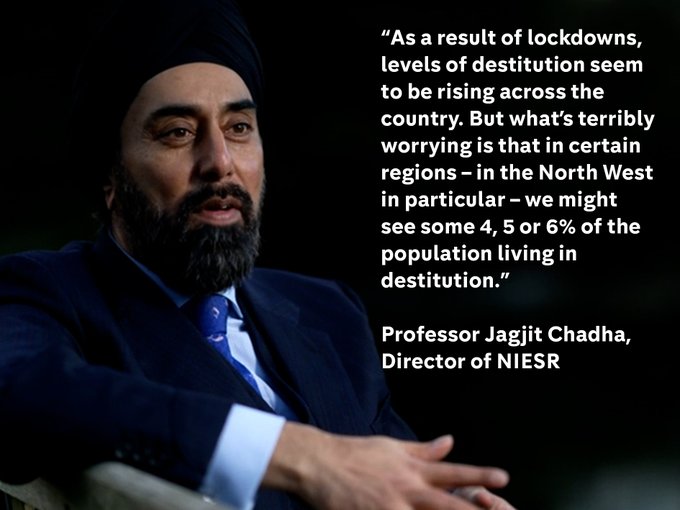

The Covid pandemic has had enormous economic effects as experts in the bleeding obvious say.

Specifically,

The number of people being made redundant in the UK is rising at the fastest pace on record as the second wave of Covid-19 and tougher lockdown measures put increasing pressure on businesses and workers.

Unemployment has hit the highest level for four years, while millions more workers have been placed on furlough. Although the jobs crisis has not been as bad as feared earlier in the pandemic, the government’s independent economics forecaster – the Office for Budget Responsibility – expects the jobless rate to more than double from pre-pandemic levels to 7.5% this summer after furlough ends, representing more than 2.6 million people out of work.

This is from the East Anglian Daily Times, yesterday.

120% increase in Universal Credit claimants

The number of claimants for Universal Credit in Babergh and Mid Suffolk has increased by 120% amid the fallout from coronavirus – with a tsunami of extra demand expected.

Citizens Advice figures presented to Babergh and Mid Suffolk district councils’ joint scrutiny committee on Monday revealed that Universal Credit claimants had gone up by 119% in Babergh and 122% in Mid Suffolk compared to December 2019.

Today the story about the looming cut to Universal Credit continues,

New Fabian Society research finds that over 700,000 people in working or disabled households are to be pulled into poverty by universal credit cuts.

The report shows how the cut to universal credit will reduce the living standards of households in many different circumstances:

- Households with a disabled adult will be hit by 57 per cent of the cuts (£3.7bn per year)

- Families with children will be hit by half the cuts (£3.2bn per year)

- Households where someone is a carer will be hit by 12 per cent (£700m per year).

Only 13% of the savings will come from non-working, non-disabled households.

95% of those hit by UC cut in working or disabled households, report finds

Elliot Chappell. Labour List.

New research has found that 95% of those who will be pushed into poverty by the cut to Universal Credit and Working Tax Credit planned by Rishi Sunak this year are in working or disabled households.

Following the publication of the Fabian Society report Who Loses? today, supported by the Standard Life Foundation, the Labour affiliate has said the £20-per-week reduction to the benefit “raises fundamental questions of justice”.

Analysis found that 87% of the cut, £5.5bn, will fall on working and disabled households, while half, £3.2bn, will hit homes where someone is in work. Households with someone in employment will make up 65% of all those pulled into poverty.

Commenting on the findings of the report, Andrew Harrop warned that scrapping the £20-per-week uplift, introduced to help people cope with the pandemic last year, will “overwhelmingly punish working families and disabled people”.

The Fabian Society general secretary added: “The Chancellor’s planned cut will strip £1,000 per year from six million families and plunge three quarters of a million people into poverty.

“Some politicians like to pretend that social security is just for the work-shy. But the reality is that millions of working households need benefits and tax credits to make ends meet, as do disabled people who are out of work through no fault of their own.

“If ministers are considering a few months’ temporary extension to the Universal Credit uplift, that just isn’t good enough. The 2020 benefit increase must be placed on a permanent footing.”

The Chancellor introduced the increase last March. It is not available to those on legacy benefits: child tax credit; housing benefit; income-related employment and support allowance; income-based jobseeker’s allowance; income support.

It took the standard rate for a single claimant on Universal Credit for those over 25 from £317.82 to £409.89 a month. The extra support, worth over £1,000 annually to each household, is currently set to be withdrawn in April.

The paper published today shows that people who are not expected to be job hunting – those already in work or disabled – will be the main long-term victims of Sunak’s insistence on scrapping the uplift.

Food Bank Britain Faces Bleak Winter.

Food banks report huge surge in demand for food parcels amid Covid pandemic

This is no surprise.

Most things like this you can see if you care to look, right bang in your area (obviously not in IDS’s manor).

As this Blog has mentioned there is a queue of people outside the Seventh Day Adventist Church in this area waiting for food on a Sunday.

This is outside of the main local Food Bank network. FIND foodbank

It is just a lot more visible to anybody in the centre of the town.

Trussell Trust reports that it has already helped more than a million people affected by the Covid pandemic.

More than a million food parcels have been handed out families and individuals in crisis since the start of the Coronavirus pandemic earlier this year, according to new figures from the UK’s largest food bank network.

The Trussell Trust, who operate more than 1,200 food bank centres, says it has helped to support over 1.2 million households who have been negatively affected by the economic fallout, caused by the outbreak.

It includes 470,000 food parcels given to parents to feed their children, a 52% rise on last year, and is equivalent to 2,600 food parcels for children being given out every day since the start of the pandemic.

There is also an article by James Bloodworth which is really really worth reading:

The Government has U-turned on free school meals. But moralising about people’s diets won’t help

When I was researching a book on low-wage Britain, I stumbled across an article in the Daily Mail about a woman who managed to survive on £1 a day. “Frugal Kath Kelly, 51, ate at free buffets, shopped at church jumble sales and scrounged leftovers from grocery stores and restaurants,” ran the story. “She even collected a staggering £117 in loose change dropped in the street.”

The story was written in admiring tones — Kath Kelly was presented as a sagacious and resourceful example to the poor. The underlying message was that the lower orders were feckless and stupid. Instead of sourcing and preparing healthy ingredients, they chose to plonk themselves in front of a television set and inhale pot noodles and multipacks of crisps.

…..

For those on low wages or benefits, poverty is the thief of time. Being poor invariably consists of countless hours spent waiting around for public transport, bosses, landlords or public sector bureaucrats. And that’s before one adds up the additional time it takes to care for a family. Even if it can be done relatively cheaply, preparing a healthy meal invariably takes longer than putting a pizza in the oven.

….

We no longer dictate the food those on unemployment benefits must consume (though the argument that we ought to is a frequent saloon-bar trope). But a peculiar moral tone to our conversations about food persists. This is not confined to one political tribe. Nowadays liberals too are often heard laying down pious strictures as to what the poor should eat and drink. Sugar taxes have been introduced and junk food advertising is set to be banned before the 9pm watershed. Newspapers such as The Guardian have called for the government to go even further in terms of regulating what people eat.

Basic Income Trials: Solution to Benefit Poverty or Mirage?

Solution or Mirage?

Support is said to be growing for Basic Income. Some of our contributors have shown interest and have noticed that this experiment is underway:

Germany to give people £1,000 a month, no questions asked, in universal basic income experiment

The Independent article says,

Researchers in Germany will give a group of people just over £1,000 a month, no strings attached, as part of an experiment to assess the potential benefits of introducing a wider universal basic income (UBI).

The radical idea has attracted a growing amount of interest around the world as a way of potentially supporting people during the coronavirus pandemic and beyond.

Advocates claim a small, regular income from the state to all citizens would help tackle poverty, encourage more flexible working practices, and allow some people to spend more time caring for older family members.

The German pilot study will initially see 120 people handed the monthly sum of 1,200 Euros (£1,085) to monitor how it changes their work patterns and leisure time.

Researcher Jurgen Schupp – who is leading the ‘My Basic Income’ project at the Berlin-based German Institute for Economic Research – said he wanted to discover how a “reliable, unconditional flow of money affects people’s attitudes and behaviour”.

The present trial follows this one in 2019.

Germany’s ‘money for nothing’ experiment raises basic income questions

250 randomly-selected recipients of Hartz IV, the bottom rate “safety net” German welfare payment, have begun to receive their monthly €416 without any conditions attached.

Hartz IV recipients have certain obligations to meet, for example, the need to keep appointments at the job center or to show evidence of looking for work. Failure to meet the conditions might see their benefits cut via “sanctions.”

For the next three years, the activist organization Sanktionsfrei (“Sanctions-Free”) will automatically reimburse any sanctions imposed on the 250 test recipients. Effectively, they will be guaranteed a basic income of €416 every month.

The participants will fill out regular questionnaires, documenting the effects of their new status. An additional 250 Hartz IV recipients will act as the control group, filling out the same form while still being subject to the usual conditions.

Strictly speaking, this endeavour, labeled “HartzPlus” is not a Universal Basic Income (UBI) experiment. For starters, it is backed by a private organization and is not supported by the German government.

…..

some observers of HartzPlus have pointed out that it is not a UBI as it is not paid if the person finds a job which pays more than the welfare claim.

The present experiment is just that, an Experiment.

Germany is set to trial a Universal Basic Income scheme

- Starting this week, 120 Germans will receive a form of universal basic income every month for three years.

- The volunteers will get monthly payments of €1,200, or about $1,400, as part of a study testing a universal basic income.

- The study will compare the experiences of the 120 volunteers with 1,380 people who do not receive the payments.

- Supporters say it would reduce inequality and improve well-being, while opponents argue it would be too expensive and discourage work.

The study, conducted by the German Institute for Economic Research, has been funded by 140,000 private donations.

Interest in Basic Income continues.

There is interest in the USA.

This was reported in July.

Twitter boss donates $3m to basic universal income project

BBC.

Twitter chief executive Jack Dorsey has become the first investor in a radical plan to give people a basic income, regardless of job status.

He has donated $3m (£2.4m) to the scheme, which is being piloted by the mayors of 16 US cities.

He said it was “one tool to close the wealth and income gap”.

The idea of governments paying a basic income to citizens has gained momentum in response to the threat to jobs from artificial intelligence

There are three basic problems with applying experiments in Basic Income to a whole country.

- Unlike social security payments they do not redistribute money by taxation from those who make extra cash out of other people, business and the wealthy, and give some of this surplus to those who have less money. Everybody gets the same basic income.

- Despite claims that Basic Income schemes would give everybody “enough to live on” no proposed system can allow for the variable and extra costs that payments under social security systems (in Europe at least) cover, Housing Benefit (local Housing Allowance), or the extra cash needed by ill or disabled people (PIP and so on). The German plans, for example, would mean that somebody who is unemployed and paying rent would still have to rely on getting welfare payments to cover housing costs that go beyond the sum given.

- Apart from not fully covering people’s needs, they do not answer a problem that unemployment brings for those who wish to work: to use our abilities as we can.

There would have to be criteria to get Basic Income – they could not be open to anybody from anywhere to come and claim.

A large proportion of public spending would go on any variety of the scheme. We would have the absurd position in which those with large private incomes would get an extra “top up” every month.

Would pensioners get the money? If this is the case we would see a huge increase in spending on the retired alone.

As Anna Coote says (Guardian. 2019. Universal basic income doesn’t work. Let’s boost the public realm instead)

The cost of a sufficient UBI scheme would be extremely high according to the International Labour Office, which estimates average costs equivalent to 20-30% of GDP in most countries. Costs can be reduced – and have been in most trials – by paying smaller amounts to fewer individuals. But there is no evidence to suggest that a partial or conditional UBI scheme could do anything to mitigate, let alone reverse, current trends towards worsening poverty, inequality and labour insecurity. Costs may be offset by raising taxes or shifting expenditure from other kinds of public expenditure, but either way there are huge and risky trade-offs.

Money spent on cash payments cannot be invested elsewhere. The more generous the payments, the wider the range of recipients, the longer the scheme continues, the less money will be left to build the structures and systems that are needed to realise UBI’s progressive goals.

The report Coote cites, Universal Basic Income. A Union Perspective, says,

At the heart of the critique of UBIs contained in this brief is the failure of the most basic principle of progressive tax and expenditure, which can be summarised as “from each according to their ability, to each according to their need”.

Whereas universal benefits such as healthcare or unemployment payments are provided to all who need it, UBI is provided to all regardless of need. Inevitably it is not enough to help those in severe need but is a generous gift to the wealthy who don’t need it. It is the expenditure equivalent of a flat tax and as such is regressive. But the consequences are more than a question of principle.

The estimates of funds required to provide a UBI at anything other than token levels are well in excess of the entire welfare budget of most countries. If we were able to build the political movement required to raise the massive extra funds would we chose to return so much of it to the wealthiest, or would it be better spent on targeted measures to reduce inequality and help the neediest?

What’s more such schemes require the total current public welfare budget to be used. Do we really want to stop all existing targeted programmes such as public housing, public subsidies to childcare, public transport and public health to redistribute these funds equally to billionaires.

UBI would erode the basis for the welfare state.

And this raises other practical political issues. With a UBI in place many have argued that the states obligations to welfare will have been met. That people would then be free to use the money as they best need – free from government interference. With such a large increase in public spending required to fund a UBI it would certainly prompt those who prefer market solutions to public provision with powerful arguments to cut what targeted welfare spending might remain.

Arguments put by proponents of UBI to counter these questions usually involve targeting of payments, or combination with other needs-based welfare entitlements. However, as this report notes, models of UBI that are universal and sufficient are not affordable, and models that are affordable are not universal. The modifications inevitably required amount to arguments for more investment, and further reform, of the welfare state – valuable contributions to public debate but well short of the claims of UBI.

It is a mirage solution.

It is one of the unfortunate mirages of UBI, as clear from the evidence and trials outlined in this report, that UBI can mean all things to all people. But the closer you get to it the more it seems to recede. A further, and significant point for trade unionists, is the assumptions UBI proponents make about technological change and the effect on workers. The argument that technology will inevitably lead to less work, more precarious forms and rising inequality is deeply based on the assumption that technology is not within human control. In fact, technology is owned by people and can be regulated

by government if we chose.Work is not disappearing – there are shortages of paid carers and health care workers, amongst others, across the globe. And precarious work can be ended at any time with appropriate laws. What is missing is the political will to control technology, and work, for the benefit of the population. In this regard UBI is a capitulation to deregulation and exploitation, not a solution to it.

If, in a sense, with the Pandemic work is disappearing. Is a massive transfer of spending from the welfare state to everybody through UBI, instead of targeted schemes that focus on maintaining employment, the answer?

The German scheme, DW noted back in 2019, has this difficulty,

The most persistent criticism that advocates of a universal basic income face is the question of cost. For example, to take a crude measurement, if the close to 70 million adults in Germany were all to receive an unconditional, universal basic income payment of €416 per month (the current Hartz IV rate), the annual cost to the German government would be around €350 billion. In a savings-obsessed country, that might prove a hard sell.

All the problems outlined above indicate that Universal Basic Income is not a solution but a mirage.

The neoliberals of the Adam Smith Institute think differently.

You must be logged in to post a comment.